Profile

- Research Subject

Researching the interpretive characteristics of Confucian classics (Jing Shu), focusing on the Modern Text School (Jinwen Xuepai) during China’s Qing dynasty. Also interested in the modern reinterpretation of these classics.

- Research Fields

- History of Chinese Thought, Qing Dynasty Scholarship

- Faculty - Division / Research Group / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Research Group of Cultural Representations / Laboratory of Sinology

- Graduate School - Division / Department / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Department of Cultural Representations / Laboratory of Sinology

- School - Course / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities and Human Sciences / Course of Linguistics and Literature / Laboratory of Sinology

- Contact

Office/Lab: 405

Email: yoshida100(at)let.hokudai.ac.jp

Replace “(at)” with “@” when sending email.Foreign exchange students who want to be research students (including Japanese residents) should apply for the designated period in accordance with the “Research Student Application Guidelines”. Even if you send an email directly to the staff, there is no reply.- Related Links

Lab.letters

Pursuing lofty principles in subtle words

within the eternal currents of Chinese thought

Mencius wrote that Confucius, lamenting the prevalence of unacceptable acts such as sons or subjects killing their fathers or sovereigns, created the Spring and Autumn Annals to transmit his teachings and ultimately also serve as both a historical record and a treatise on philosophy. These obviously unacceptable acts, or the subjects of lofty principles, are paired with the subtle sayings that expound upon the principles and methods of governing the realm. The content is considered difficult to grasp, and as such, its interpretation varies across eras and scholarly schools. We trace how Mencius interpreted Confucius’ teachings, and how Qing dynasty thinkers interpreted the works they left behind. And in doing so, we seek to grasp the grand currents of Chinese thought through the lineage of knowledge in China, a land of enduring history.

Influenced by the research ethos around me,

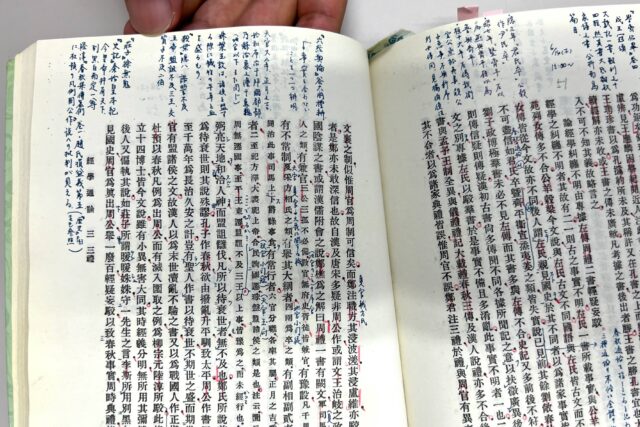

I became part of the lineage of reading carefully.

Our Laboratory of Sinology also carries on a long-standing intellectual lineage of delving into Chinese thought. In fact, what sparked my immersion in my current research, back when I was a student at Hokkaido University, was none other than the fact that the professors at this Laboratory personally compiled and preserved a Japanese translation of Pi Xirui’s Sanli Tonglun (A General Discussion of the Three Rites), a work that had not yet been translated in Japan. Precisely because it is not an explosively popular field, the guidance given to each individual is meticulous, and interaction among graduate students is vibrant. I feel that the most crucial research attitude, the stance of reading materials carefully, was something I learned naturally by observing the daily research practices of my professors and more experienced students. I now approach my work with the conviction that it is my turn to pass on that tradition to you all.

Message

During my graduate school days, I participated in a reading group with students from the Laboratory of Sinology. We studied Pi Xirui’s Jingxue Lishi (The History of Classical Scholarship) and Jingxue Tonglun (A General Discussion of Classical Scholarship), which are considered both introductions to Confucian studies research and classic masterpieces. While reading books deeply on one’s own is important, I believe reading together with like-minded peers is equally valuable. The Liji (The Book of Rites) also states that “studying alone without friends” is not a good thing. The Laboratory of Sinology provides not only classes, but also an environment for growth and opportunities to find peers to learn with, as I did, if you wish. Moreover, the influence of China’s classics, language, culture, and institutions on Japan is immeasurable, extending far beyond the Confucian classics. Living in Japan, we often find ourselves immersed in this influence without even realizing it (the phrase “unwittingly” itself has an example in the Shijing (Book of Songs). Therefore, I sincerely hope that not only those interested in China, but also those who wish to understand Japan more deeply, will come and knock on the door of the Laboratory of Sinology.