Profile

- Research Subject

I specialize in modern Japanese history, focusing chiefly on the relationship between the Imperial Household and visual media from the Taisho era through the early pre-war Showa period. My research also examines kokusaku kamishibai—state-sponsored picture-story shows produced as propaganda during the Asia-Pacific War. I have also published scholarly articles documenting the activities of each of the three peace museums where I have worked.

- Research Fields

- Modern Japanese History, Museum Studies

- Faculty - Division / Research Group / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Research Group of Cultural Diversity Studies / Laboratory of Museum Studies

- Graduate School - Division / Department / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Department of Cultural Diversity Studies / Laboratory of Museum Studies

- School - Course / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities and Human Sciences / Course of Philosophy and Cultural Studies / Laboratory of Museum Studies

- Contact

Email: koyama(at)let.hokudai.ac.jp

Replace “(at)” with “@” when sending email.Foreign exchange students who want to be research students (including Japanese residents) should apply for the designated period in accordance with the “Research Student Application Guidelines”. Even if you send an email directly to the staff, there is no reply.

Lab.letters

Getting a feel for an era through the story behind

Imperial Family photographs and state-sponsored picture-story shows

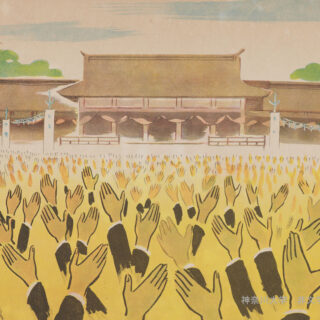

[Thumbnail image] Picture-story: Shinnmin no Michi (Way of Subjects) / Image source: Kanagawa University Research Center for Nonwritten Cultural Materials

The Imperial Household Agency now shares Imperial Family news via its official Instagram account, but until the end of the Meiji period, Emperor Meiji reportedly disliked having his photograph taken. Consequently, media outlets were not permitted to photograph the Emperor or Imperial Family members for news coverage, except for the official photographs known as Imperial Portraits. One catalyst for the relaxation of those regulations was Crown Prince Hirohito’s overseas tour in 1921. How did the correspondents, who were not even permitted to board the same ship, conduct their reporting and filming, and how did they disseminate their coverage? I am interested in the trends and intentions of those involved that lie hidden behind the actual photographs, and in how the photographs were received. I also examine wartime state-sponsored picture-story shows through a similar lens, tracing the relationship between visual media and society that flourished in modern Japan.

Sharing with the world through the work of

diverse researchers and curators

The postwar 50th anniversary coverage I saw and heard as a junior high student left a deep impression on me. I have pursued both historical research and museum studies, all the while keeping the question in my heart of, “What exactly was that war?” Research and museum exhibitions in fields such as peace research based in Hiroshima, where the suffering of those affected continues to this day, always demand a sincere approach from researchers and curators. I believe that research fields meant to be widely known among diverse audiences thrive when researchers from varied backgrounds gather to interpret materials from their unique perspectives, thereby cultivating the significance and value of both research and exhibitions. Looking beyond Tokyo, often seen as the center of both political and economic power, and inquiring into the other regions of that era also enhances our ability to understand society with greater resolution.

Message

At university and graduate school, I specialized in modern and contemporary Japanese history, focusing primarily on the relationship between the Imperial Family and visual media from the Taisho era through the pre-war Showa period. I have also participated in collaborative research on state-sponsored picture-story shows, a form of propaganda media deployed during the Asia-Pacific War period.

In parallel with this research, I have served for over 15 years in three museums related to the Asia-Pacific War. It is well known that compared to the specialized roles in the West, Japanese curators are often called jacks-of-all-trades because they are overwhelmed with all kinds of duties. I was no exception, having been involved in each of the museum’s fundamental functions, albeit with varying degrees of emphasis. This included collection, preservation, exhibition, education, and surveying and research.

Working at a museum naturally leads one to view society through the window of the museum. Museums exist within society and are subject to various influences stemming from societal changes. What does a museum mean to society? How can we gain insight into society from the perspective of a museum? These are not easy questions, but I wish to explore them together with everyone gathered at the Laboratory of Museum Studies.