Profile

- Research Subject

Political history research based on ideological and institutional issues regarding various aspects of state management under the Meiji Constitution.

- Research Fields

- History of Japan

- Faculty - Division / Research Group / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Research Group of History / Laboratory of Japanese History

- Graduate School - Division / Department / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Department of History / Laboratory of Japanese History

- School - Course / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities and Human Sciences / Course of History and Anthropology / Laboratory of Japanese History

- Contact

Office/Lab: 514

TEL: +81-11-706-2849

Email: aki-kawa(at)let.hokudai.ac.jp

Replace “(at)” with “@” when sending email.Foreign exchange students who want to be research students (including Japanese residents) should apply for the designated period in accordance with the “Research Student Application Guidelines”. Even if you send an email directly to the staff, there is no reply.- Related Links

Lab.letters

Constitutional revisions were made 18 times in America and 119 times in Switzerland, while one phantom constitutional revision was made in Japan.

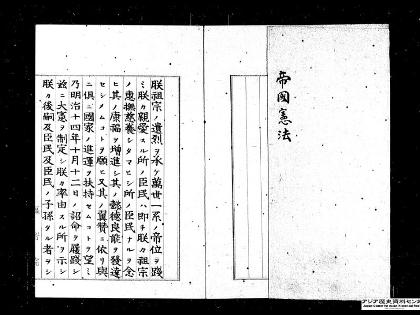

It’s common for countries around the world to revise their constitutions: America has done it 18 times, Germany 43 times, Switzerland as many as 119 times and Japan once. The Constitution of Japan is a revised version of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan. However, few Japanese know about this phantom constitutional revision. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan, which was promulgated in 1890, was effective until 1946. The Constitution of Japan was enacted in 1947 and has remained in effect since then. It seems likely that we Japanese have a peculiar propensity for sticking to a constitution once it’s been created, without revising it. My studies aim to clarify the reason for this interesting phenomenon.

Reconsider common sense through research on a topic you find fascinating.

It’s common sense in international society that a constitution should be revised according to the trends of the times, but this doesn’t apply to Japan. What is most inspiring in this discipline is to clarify on your own what the world is all about – the world that comes into sight after one reconsiders commonsense views. I’m afraid that leaving others to select your research theme or seeking a shortcut for your research without any effort can’t be conducive to your growth. Fortunately, Hokkaido University is blessed with a calm environment where students can think with composure, as well as with upper and lower classmates who can give encouragement. I’m pleased to support you by providing lectures rich with the fascination of the Meiji Constitution so that I can help boost your enthusiasm for research.

Message

I have been engaged in research on modern Japanese history with a particular focus on delineating the history of trends related to the Meiji Constitution based on “the constitution never worn thin.” I began with the History of the Meiji Imperial Constitution and submitted Two Constitutions and the Japanese as my interim report.

Currently, my research is focusing on how Japan and the Japanese people considered and treated political offenders in modern Japan. My previous research dealt with the history of those who affirmatively accept the nation, ignoring those who deny it. This stance is not conducive to grasping a complete picture of modern Japanese history.

Political offenders in the Meiji era (1868–1911), also called political criminals, were regarded as heroes by the public. The Meiji government treated them severely in some cases and leniently in others. Those in the Showa era (1927–1987), also called ideological criminals, were stigmatized by society. The government encouraged conversion as an opportunity to reflect on their actions. Studies reveal that the image of political offenders in modern Japan shifted from objects of awe to social dropouts. Exploring the historical factors in such a transformation is my current mission.