Profile

- Research Subject

a study of exprression and structure about Narrative Collecions made on the medieval period

- Research Fields

- narrative literature

- Faculty - Division / Research Group / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Research Group of Cultural Representations / Laboratory of Pre-modern Japanese Literature and Culture

- Graduate School - Division / Department / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Department of Cultural Representations / Laboratory of Pre-modern Japanese Literature and Culture

- School - Course / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities and Human Sciences / Course of Linguistics and Literature / Laboratory of Pre-modern Japanese Literature and Culture

- Contact

Office/Lab: 419

Foreign exchange students who want to be research students (including Japanese residents) should apply for the designated period in accordance with the “Research Student Application Guidelines”. Even if you send an email directly to the staff, there is no reply.- Related Links

Lab.letters

Collections of narratives that have been passed down to the present like a telephone game: Focus on the relationship between writer and reader

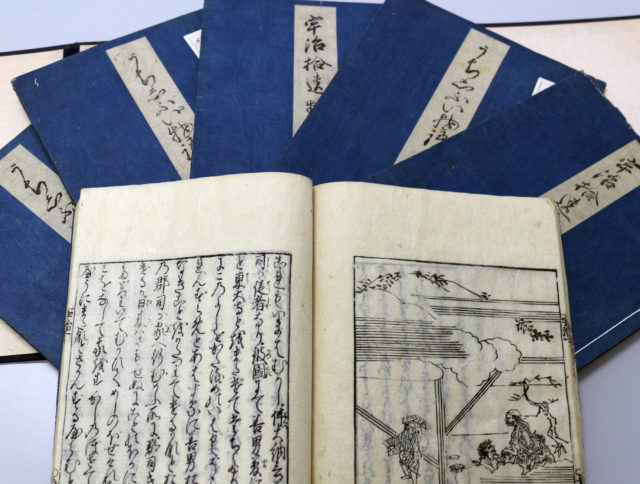

Jukkinsho (The Miscellany of Ten Maxims) and Uji Shui Monogatari (A Collection of Anecdotes from Uji), produced in the early 13th century, are collections of narratives. Unlike stories, these collections have unique characteristics: They consist of a relatively short, single piece of information that has been passed down from person to person as in a telephone game. How does a writer who was once a reader try to convey some information to the next reader? The attraction derived from interpreting narrative works while imagining the relationship between writers and readers can surely be found in research on collections of narratives. For example, Jukkinsho makes the reader feel a duality of lessons: the lesson of each anecdote, and the lesson of the collection as a whole. I’m working on interpreting the work while considering the multiple intentions of the writer.

Research on collections of narratives full of familiar subjects, serving as training for multiple interpretations of information

When one speaks of classical literature and ancient writings, people tend to think of them as offerings at the household altar, remote from daily life. I sincerely hope that we can get these offerings off the altar and treat them as parts of ordinary daily conversation. In particular, narrative collections contain many subjects that any reader can feel familiar with, and they hold the potential for themes that researchers have not come up with yet in detailed parts of these collections. I believe research on collections of narratives itself serves as training to consider an item of information from multiple perspectives.

The greatest driving force behind your research at a university is to develop a feeling of curiosity. I’m willing to help you soundly cultivate the seeds of that curiosity within you.

Message

There is an anecdote about Fujiwara no Teika, a poet representative of the medieval period, that says when others admired his poems, he showed displeasure on his face. This episode indicates his character and the stubborn nature of poets or other artists, which makes me sense the difficulty of words. Whether it is a waka poem or admiration, the routes taken by messages include various bottlenecks. Though it may be an immature way of thinking, I am inclined to empathize with written materials from the past. At the same time, I am keenly aware that I must face my illusion of such empathy. Consideration of the gap between conveying and being conveyed can be equated to facing a subject head-on while questioning whether or not it is true. I think the task of understanding classics can be compared to traveling to seek out words yet unknown to you in words narrated by others.

Medieval times were also a period for which I was worried about how I should face stories and waka poems written in the previous period. Why not join us in striving to understand unknown words from medieval Japan?