Profile

- Research Subject

I am in charge of pre-Modern Chinese history. My specialty is the history of society and thought of the Song dynasty, and I am pursuing how the shi-da-fu class, which was the knowledge class at that time, has changed in the long span from Tang to Ming, based on the interaction between society and thought.

- Research Fields

- history of society and thought of the Song dinasty

- Faculty - Division / Research Group / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Research Group of History / Laboratory of Oriental History

- Graduate School - Division / Department / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities / Department of History / Laboratory of Oriental History

- School - Course / Laboratory

- Division of Humanities and Human Sciences / Course of History and Anthropology / Laboratory of Oriental History

- Related Links

Lab.letters

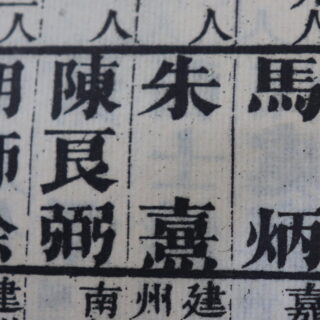

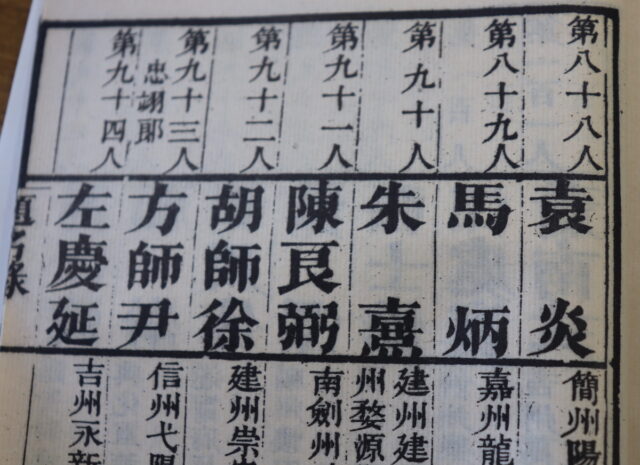

Looking at the connection between kakyo (ancient Chinese higher civil service examinations) that served as a driving force to change China and schools / local communities

The kakyo examinations, which were expanded in the Song Dynasty, played a significant role in transforming Chinese politics and society. As the kakyo system spread, the number of examinees exploded. Consequently, the local schools where they gathered gradually began to function not only as institutions where Confucian rituals and ceremonies took place but also as places providing opportunities to build networks of connections through which they could promote themselves for future career advancement in the capital city as well as hubs for local communities where influential persons and intellectuals interacted with each other. The kakyo examinations were too difficult to pass, making a number of examinees face the question—one that would follow them even after failing the test—of how they should lead a meaningful life going forward. Humanities is a discipline that identifies the relationship between humans and society, an aggregate of humans. My research also focuses on identifying the effect the Chinese epoch-making kakyo system had on people as well as its involvement in Chinese society.

Exploring unwritten backgrounds from historical papers written in <i>kambun</i> (Chinese classics)

It will take you quite some time to successfully peruse historical sources written in Chinese classics, and I believe the shortest route to accurately understanding such documents is to develop intuition by reading an extensive array of Chinese classics. Historical papers created by Chinese intellectuals are written based on the implicit assumption that readers have already acquired the ability to understand documents as typified by shishogokyo (the Four Books and Five Classics of Confucianism). Therefore, understanding even a single word requires the capacity to interpret the unwritten background behind it. While at first you may feel as if you are delving into mysteries, the more you read, the more expertise you will acquire. This will certainly lead you to fruitful research with originality.

Hokkaido University has a tradition of research on Chinese history, and my laboratory welcomes those who are interested in not only the Song Dynasty but also other diverse themes. I look forward to your visit to the world of historical sources in Chinese classics, which are interesting because of just how deep you can delve into them.

Message

The world of historical documents in Chinese classics

To briefly sum it up in my own words, the appeal of Chinese history is the sheer amount of written documents that exist. Chinese regions can be described as developed areas boasting affluent economies, large populations and advanced civilizations. Their emphasis on keeping written records has made it possible to successfully maintain a wealth of written documents. While interpreting them is harder than expected, simple sentences can stereographically shape themselves as you are exposed to a host of historical papers. You will then gradually come to understand the realities intuitively felt by people in the past.

What is Chinese history?

So what exactly does “China” refer to? It does not simply refer to the present government of the People’s Republic of China, and its ruling area is not always constant. Generally, it refers to the eastern region of the Eurasian continent. Recent research, however, has revealed that China’s history has developed in constant conjunction with the central part of the Eurasian continent and the marine world of Southeast Asia. Successfully combined with historical documents from central Asia, Europe and Japan other than Chinese classics, you may be able to identify major relationships connecting the world.

In any case, Chinese history is a vast discipline with a wealth of written documents and a diverse range of research subjects. I would like you to explore how to better understand those who lived in the past and the society they created from your own perspective.